The packaging for beverages with the lowest carbon footprint is aluminum cans, but many beverages (especially juice) just aren’t available in aluminum. So, why not glass? When I was a kid, nearly every beverage you could buy at the store came in glass bottles or steel cans. Today, glass is my go-to packaging of choice, if aluminum isn’t an option. Why glass, you ask?

For one, like metal, glass is nearly infinitely recyclable. Plastic isn’t, and although I can faithfully take my #1 and #2 plastic to the recycling station, I know that it will not likely be recycled into new bottles, but rather into “secondary” plastic products such as toys or carpeting. And forget about other plastics, such as #6 (polystyrene) as I have written about earlier.

The main reason for my resolution to avoid single-use plastic is because of the environmental effects of waste plastic in the environment. But reducing my overall carbon footprint is also a worthy goal.

When I went to the recycling station this weekend, I expressed my pleasure (relief?) that they were still accepting glass. They collect colorless, brown, and green (“includes gray, blue and purple”) glass separately. The weekend attendant said that they sent it somewhere in Oklahoma. I found this interesting, because a friend alerted me to the fact that the waste collector Republic Services in central Oklahoma stopped collecting glass as of January 1, along with plastics coded #3-7. The company line was that the “carbon footprint to collect, transport and recycle glass now exceeds the benefit of recycling it. It is no longer environmentally responsible to recycle glass.”

Nice try. It’s more likely that the current infrastructure doesn’t make it profitable for them, and rather than look for alternatives, they’re simply getting out of the business altogether. Case in point: Colorado’s largest glass recycler, MillerCoors’ Rocky Mountain Bottle Company, recently dropped the price they were paying for single-stream, mixed color glass from $60 to $20 per ton. However, this is mainly because a new company is providing them high-quality, color-specific crushed glass called cullet. In other words, a new market emerged with a better product. (Footnote: a local cooperative was formed last month in central Oklahoma so that residents can continue to recycle their used glass.)

And OKC is not alone: last month, Baltimore County, Maryland, revealed that the glass they have collected for the last 7 years has not actually been recycled.

The glass recycling infrastructure in the US isn’t in good shape. Of the 10 million tons of glass Americans discard each year, only about one-third gets recycled. This compares to a 90% glass recycling rate in much of western Europe. The best recipes for new glass actually include recycled glass as a key ingredient. And for each 10% of glass that comes from recycled cullet, CO2 emissions are reduced by 5%.

The multistream recycling model, in which consumers separate their own recyclables, helps. The cullet produced from a single color of glass brings a higher price and helps create better products. This is why MillerCoors switched to using it, purchasing 80% of the supply of the local supplier that opened in 2016. About 10 years ago, Boulevard Brewing in Kansas City helped launch a local cullet supplier, and placed 60 glass collection boxes around the metro area. KC locals have gotten on board, regularly supplying the cullet plant, Ripple, with clean, high-quality recyclable glass. Ripple sends most of its product to the local Owens-Corning fiberglass plant, but a significant amount is recycled into new bottles for Boulevard. The US needs more of this.

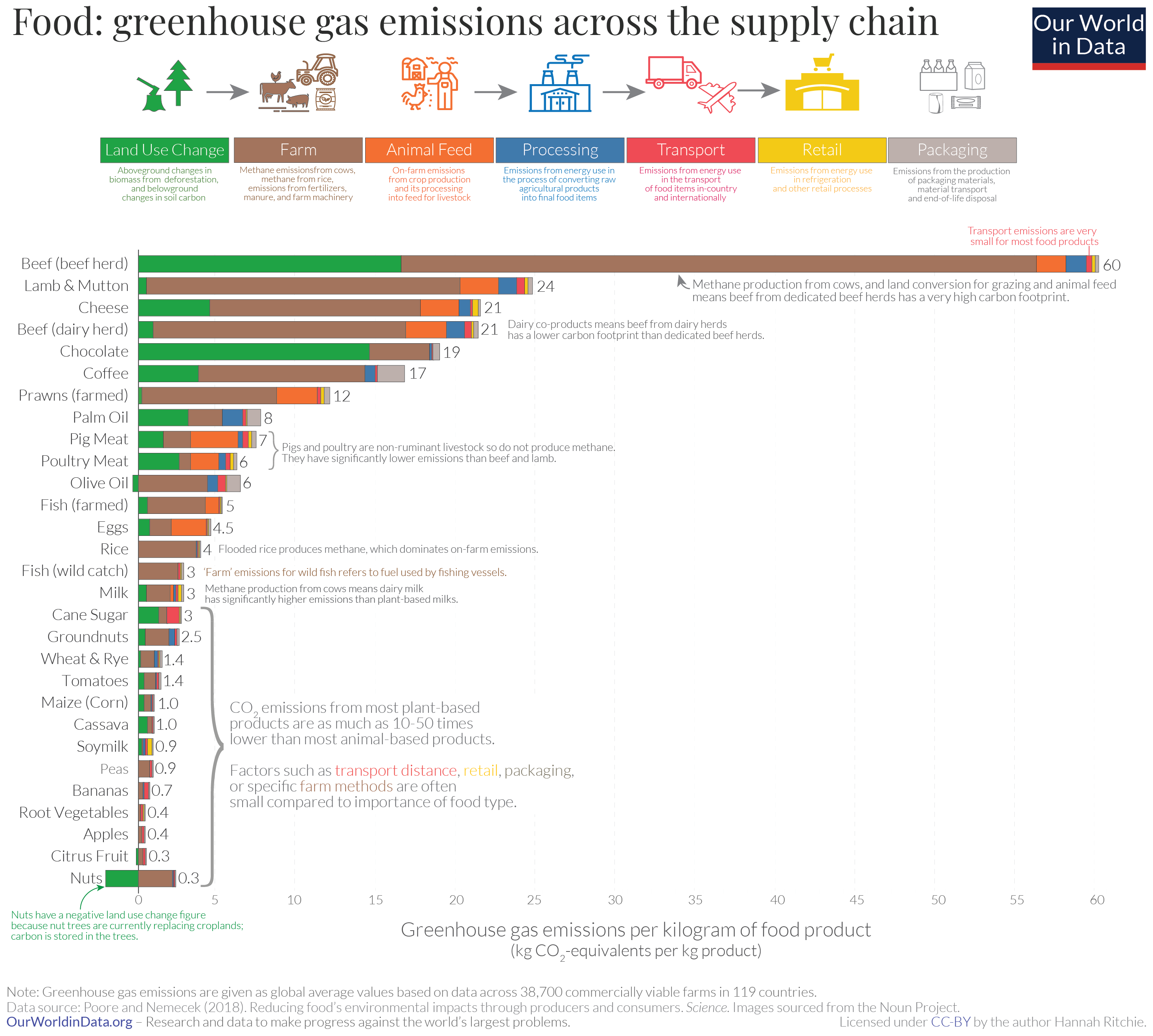

Another thing that people often wonder is if glass is truly a better option than plastic. Doesn’t glass cost more to transport? Well, yes it does. However, if we do it right, glass never has to end up in a landfill. And I was surprised to discover that, except for perishable and frozen produce, the cost of transportation of our food products is actually a very small percentage of the total impact on greenhouse gas emissions.

Recent comprehensive scientific studies in the US and the EU show that if “You want to reduce the carbon footprint of your food? Focus on what you eat, not whether your food is local.” This is because most of the greenhouse gas emissions from food production are attributed to the actual production of the food, and the loss of the land for what might otherwise be carbon-negative uses (such as trees in a forest that store up carbon). On average, as long as you avoid food that is air-freighted, such as berries, greenhouse emissions due to transportation amount to only 6% of the total impact from farm to table. Suppose the impact on transporting food products in heavier, fragile glass rather than plastic doubles the emissions from the transportation. Still, on average, this would make the transportation add up to less than one eighth of the total carbon footprint. An example from the source above states that “Shipping one kilogram of avocados from Mexico to the United Kingdom would generate 0.21 kg CO2 eq in transport emissions. This is only around 8% of avocados’ total footprint.”

A few weeks ago, I was able to find a tiny jar of mayonnaise in glass. But when I went back, it was plastic, plastic everywhere. I can get mustard in glass (pardon me, but do you have any?). For ketchup and mayo, my only options seem to be organic versions at the natural foods store. So, that’s what I’m doing. But we could make a much bigger impact if we would go back one R to the reuse stage of the refuse, reduce, reuse, recycle… series.

In the 1920s, Coca-Cola introduced a two-cent deposit on reusable, refillable glass bottles, roughly 40 percent of the full 5-cent cost of a Coke and a smile. About 98 percent of the bottles were returned, to be reused 40 or 50 times. I remember when the public works building in my small town was the RC Cola bottling plant. It was (and still is) less expensive to transport the cola syrup long distances, and then transporting the filled bottles only the shorter distance from local bottling plants such as this one to stores. We could try to move back to this kind of model. I feel powerless to make a difference in this area, but I’m trying.

A story I read in National Geographic last week used the Coca-Cola model mentioned above to introduce a story about Loop, a company started less than a year ago that ships you products that you already use in your household–such as Cascde dishwasher detergent and Häagen-Dazs® ice cream–in reusable, returnable containers. They are marketing this as a zero-waste solution, and are partnering with not only manufacturers, but also retailers such as Walgreens and Kroger. Their website states that their service is currently available in the Mid-Atlantic United States and Paris, and will expand later this year across the United States and internationally, including the United Kingdom, Canada, Germany, and Japan. How interesting! I’m concerned about the relative impact of shipping individual items to residences rather than shipping in bulk to the grocery store. But this is innovative. If we’re going to make a real reduction in plastic use, we need some innovation.